In a far-reaching report released on 19th September, the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council said the killings of nine Hindu men were part of a wave of anti-Hindu “communal atrocities” raging through the nation following Sheikh Hasina’s ouster six weeks earlier.

But an investigation by Netra News found none of the deaths bore clear signs of religious or sectarian motives. Instead, seven of the fatalities resulted from a mix of political retribution, mob violence, and criminal homicides. In some instances, the Unity Council’s assertions were undercut by the very news reports they cited and by their own grassroots officials.

Netra News has drawn its assessment from over two dozen first-hand interviews—including conversations with witnesses, family members and associates of the deceased, local journalists, public officials, and even regional Unity Council members—as well as official records, social media posts, previously unpublished media interviews, and numerous press accounts.

Assaults targeting minority groups are not uncommon in Bangladesh, including when the government changes hands. However, the violence in the days leading up to and since Hasina’s fall on August 5th has indiscriminately affected the nation of 160 million. During the period covered by the Unity Council’s report, more than 150 people—mostly Awami League activists and police officials—were reportedly killed as Sheikh Hasina’s fall precipitated a hunt for retribution and revenge. This followed her government’s ferocious handling of a student protest, which had claimed over 700 lives.

Fewer than three dozen people—around 3% of the estimated 1,000 killed before and after August 5th—are likely to have been Hindus, according to estimates by Netra News based on government records and newspaper counts. This proportion is much lower than the 8% share of Hindus in the Bangladeshi population. Yet, the Unity Council specifically singled out nine of the Hindu deaths as being motivated by communal or sectarian hatred.

The local press has uncovered sporadic attacks that appeared to target Hindu businesses, homes, and livelihoods, creating a deep sense of fear and panic within a minority community that has historically been a major source of support for Hasina’s Awami League party. Little evidence, however, points to systematic anti-Hindu atrocities orchestrated by coordinated Muslim groups.

In recent months, the Unity Council’s messaging has gained widespread traction. Between August 6th and October 12th, users on X (formerly Twitter) shared the Council’s statements to a combined following of over 11 million, according to a Netra News analysis. From August 1st to October 26th, Google News indexed at least 133 English news articles featuring the Unity Council, including from respected publishers such as Reuters, the Associated Press, and Al Jazeera.

Activists from the Unity Council and its partners in Washington D.C. inundated the mailboxes of US Congress members’ offices with messages, according to two Congressional staffers. In New York, the organisation’s US chapter arranged for a digital billboard that calls for “the killings” to stop.

International attention followed. US and European representatives referenced the report during meetings with their Bangladeshi counterparts, according to a senior Bangladeshi official. On October 16th, Raja Krishnamoorthi, a US Congressman from Illinois, cited the report in a letter to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

The Unity Council did not respond to multiple requests for comment, including when Netra News sent a detailed set of questions alongside its findings on each of the cases.

Monindra Kumar Nath, a senior official of the Unity Council, provided the 136-page report documenting thousands of alleged anti-Hindu incidents—from harassment to acts of violence as grave as murder. Netra News focused on scrutinising the most severe claims—the killings of nine men—and did not review the thousands of other violent incidents reported.

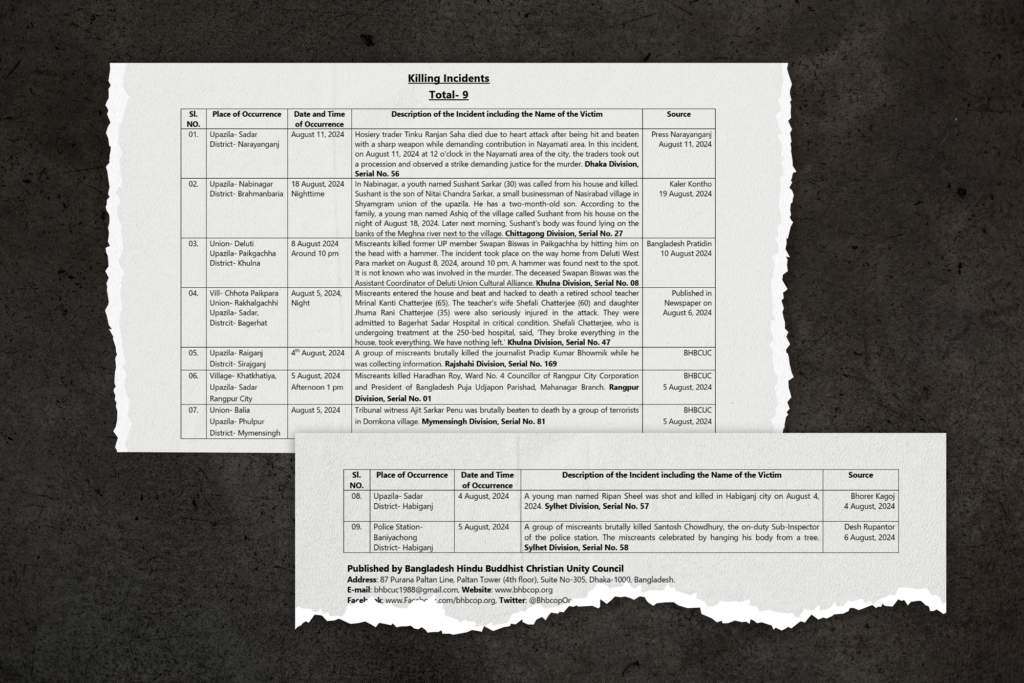

At least three individuals on the list died on August 4th, a day before Sheikh Hasina’s government was overthrown; three others died on August 5th. Only three deaths occurred after her government’s collapse. The report offers no explanation for starting its documentation from August 4th.

Moreover, the report lacks a methodology to distinguish religiously motivated killings from deaths of individuals who happened to be Hindus but were victims of ordinary crimes, political unrest, or mob violence.

This flawed approach has a history of being employed in documentations of anti-Hindu violence in Bangladesh.

In 2002, after an election in which the Awami League lost by a large margin, widespread accusations of anti-Hindu violence followed. While many of the accusations likely had a basis, the US State Department’s Bangladesh country report on human rights noted at the time that field investigations by independent human rights organisations found stories of alleged religious persecution of minority communities were, in some cases, “exaggerated” and inflated with “common criminal incidents.”

Politically charged killings

When the Unity Council unveiled their report at a press conference, Ranjan Karmakar, a presidium member of the organisation, asserted that they had excluded cases of politically motivated violence targeting members of the ousted Awami League regime—which included many Hindus among its ranks—but offered no explanation on how this distinction was made.

Contrary to their claim, Netra News’s investigation found that political motivations appeared to be a significant factor in at least some of the deaths.

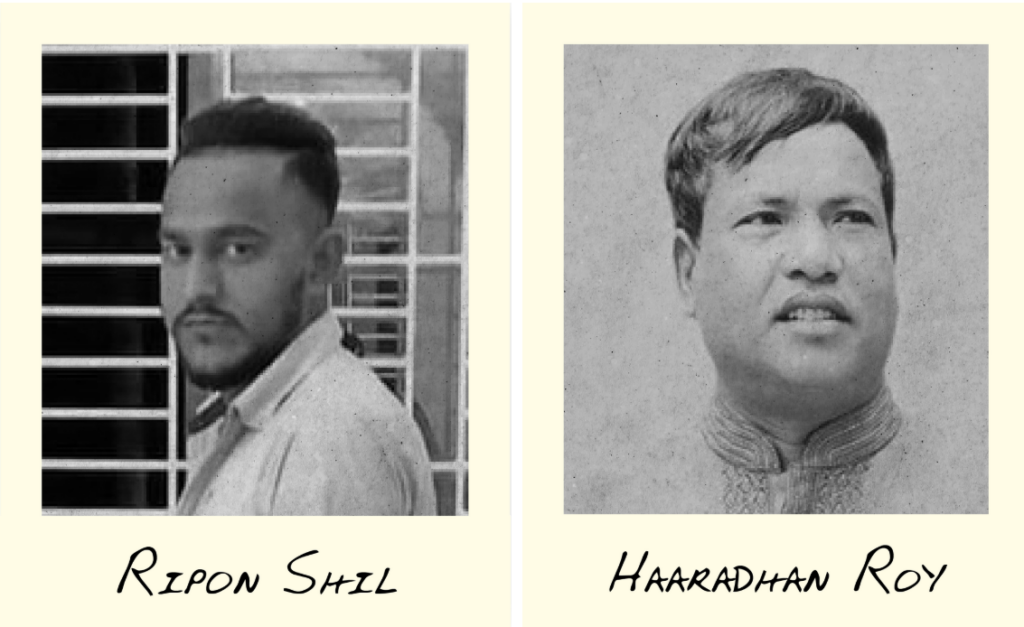

Take the case of Ripon Chandra Shil, an activist with the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) in the northeastern city of Habiganj. He participated in anti-Hasina protests and was allegedly shot dead by Awami League activists.

“We went to the protests together. I got shot in the leg. At the hospital, I found out my brother was gone. He fought for our country and sacrificed his life,” said his brother, Shipon Shil, to The Daily Star. “My brother was with the Chhatra Dal for a long time,” added his sister, Champa Shil, referring to the student wing of the BNP, in a recorded message to Netra News.

Yet, the Unity Council’s description omits Shil’s political affiliation, failing to mention his BNP ties or that he was allegedly killed by Awami League activists. Neither the Unity Council nor interviews with his family or political colleagues provided any rationale for classifying his death as religiously motivated, beyond the fact that he was Hindu.

Another individual on the list with political affiliations was Haradhan Roy, also killed on August 4th. Roy was a local city council member from the Awami League in Rangpur, a northern city.

Netra News obtained the police complaint filed by Roy’s wife, Kanika Rani, on 2nd October. The complaint describes how Roy and Fattah alias Sabuj, a Muslim Awami League activist, were chased by an angry crowd during intense street clashes. “As Awami League leaders and activists retreated, the 400–500 strong unidentified angry mob captured my husband, Haradhan Roy Hara, and Fattah […] then killed them by beating and stabbing,” the complaint known as the First Information Report reads. At least four men, all Awami League activists including Roy, were killed in the incident, the other three being Muslim.

Following the incident, Hindu community leaders, including those from the Unity Council’s local chapter, held a press conference to dispel social media rumours of a Hindu temple attack. They emphasised that while they deplored the deaths, they saw no communal motivation behind the killings. Two Hindu community leaders confirmed to Netra News that they stood by their statements but requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

The Unity Council’s report cited itself as the source of the information, but a top official of the Unity Council’s local chapter told Netra News he specifically informed the central leadership that Roy’s death was a case of political violence, not religious hatred.

Criminal Acts

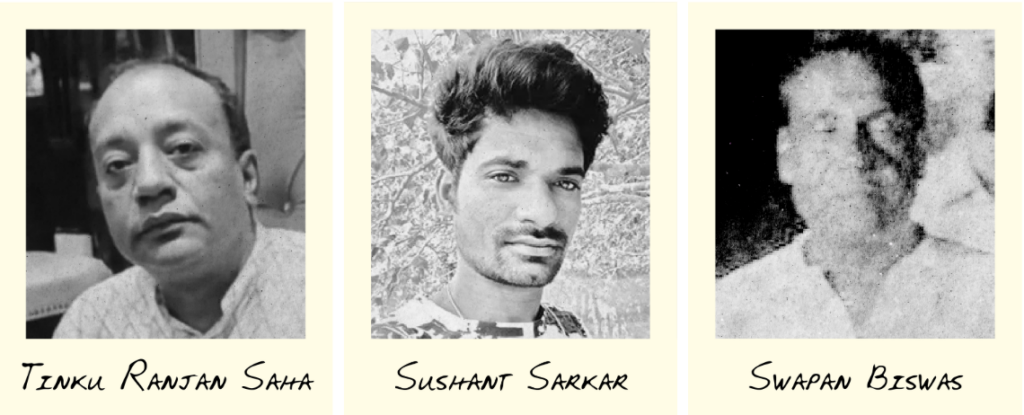

One of the first incidents documented by the Unity Council involves the death of Tinku Ranjan Saha, a hosiery trader in Narayanganj on the outskirts of Dhaka. However, the press report from a local news website cited by the “killing incidents” list suggests the incident may not have been a homicide at all.

Saha was reportedly threatened by local criminals demanding extortion money. Following this alleged intimidation on August 7th, he suffered a stroke and died four days later in a Dhaka hospital. Badiuzzaman Badu, a Muslim leader among the hosiery traders in Narayanganj, told Netra News that he has been in touch with Saha’s family. “At that time, the criminals were asking for extortion from many local leaders,” he said, noting that Muslim traders were also targeted.

Saha’s death ignited anger within the trading community, leading to protest rallies. Asit Barun Biswas, a local city councillor who presided over one such rally where fellow Muslim traders spoke passionately, also blamed extortionists. “What I know is someone tried to extort him, and he became sick after that and died a few days later,” he told Netra News. Rinku, Saha’s younger brother who also spoke at the event, blamed the criminals.

Press Narayanganj, the local news outlet cited by the Unity Council, quoted local trader Pranab Roy, who also blamed extortionists, including a ’source’ of police.

On August 18th, in Brahmanbaria, eastern Bangladesh, a young man named Sushanta Sarkar was killed. Kaler Kantho, a national newspaper cited by the Unity Council, did not categorise the killing as sectarian.

The report noted that a man identified as Ashiq lured Sarkar out of his home at night; his body was found on the banks of the Meghna River the following day. However, as with the Narayanganj case, the Unity Council omitted the potential motive included in its source: a payment dispute over a motorbike sale.

Netra News spoke to Sarkar’s mother, Rupali Sarkar, who stated that Ashiq, the alleged killer, had been friends with her son, dismissing any religious motive. A local news website identified Ashiq as Ashiq Mian.

According to Rupali, Mian had purchased her son’s motorbike for BDT 30,000 (approximately $300) but failed to pay on time. When Sarkar demanded the money a few days before his death, Mian allegedly threatened him over the phone. “I even told them not to quarrel over the money,” she told Netra News. “If he doesn’t pay the money, so be it.”

“But he killed my son for only BDT 30,000,” she alleged. Her account aligns with the Kaler Kantho report cited by the Unity Council and corroborated by ten other news reports reviewed by Netra News.

Rupali also claimed that Mian had been involved with the Awami League, a claim Netra News could not independently verify. Uttaradhikar 71, a local news website, also identified him as an Awami League member. She filed a police complaint naming Mian and five other individuals as suspects.

Family members and community leaders organised a protest rally a day after Sarkar’s death, attended by the chairman of the local Union Parishad and some leaders of the BNP, suggesting they also believed Mian was affiliated with the Awami League. The protesters carried banners displaying Mian’s photo, and speakers reiterated the same claim, according to multiple local news reports. Two Facebook videos of the protest showed local residents accusing Mian of being a known extortionist. The police arrested three people in connection with the killing.

On August 8th, Swapan Biswas, a former Union Parishad member backed by the Awami League, was killed while returning home from a local market in Paikgacha, Khulna. Locals discovered his body bearing marks consistent with hammer blows. Overwhelmed by volatile political circumstances, the local police were unable to investigate the death or examine his body. The family held a cremation the following day.

“He was attacked at midnight in a quiet place. It is difficult to ascertain who attacked him and why,” said a Hindu local government representative who wished to remain anonymous.

If it was a homicide at all, three community leaders and local journalists suggested two plausible motives: a legal dispute over shrimp farming and a conflict over land and a shop. A news report from Kaler Kantho, citing locals, suggested a similar dispute as a possible reason behind his death. Shrimp farming has a fraught history in the tiny coastal locality near the Bay of Bengal. A local movement against commercial shrimp farming emerged after the killing of Karunamayi Sardar, a local activist allegedly murdered by commercial farmers in the 1990s—a day still commemorated by a cultural organisation with which Swapan was associated.

In a telephone interview, Tripti Ranjan Sen, general secretary of the Unity Council’s Paikgacha upazila chapter, acknowledged uncertainty about the nature of Biswas’s death, let alone identifying who could have been blamed. “Some said when he was returning home, he was attacked with a hammer, while some said he fainted on the road and had a heart attack,” he told Netra News. A journalist by profession, Sen said he reported the death to the Unity Council’s central committee but confirmed he could not ascertain whether the death, if a homicide, had any communal or religious motivation at all.

Mob Violence

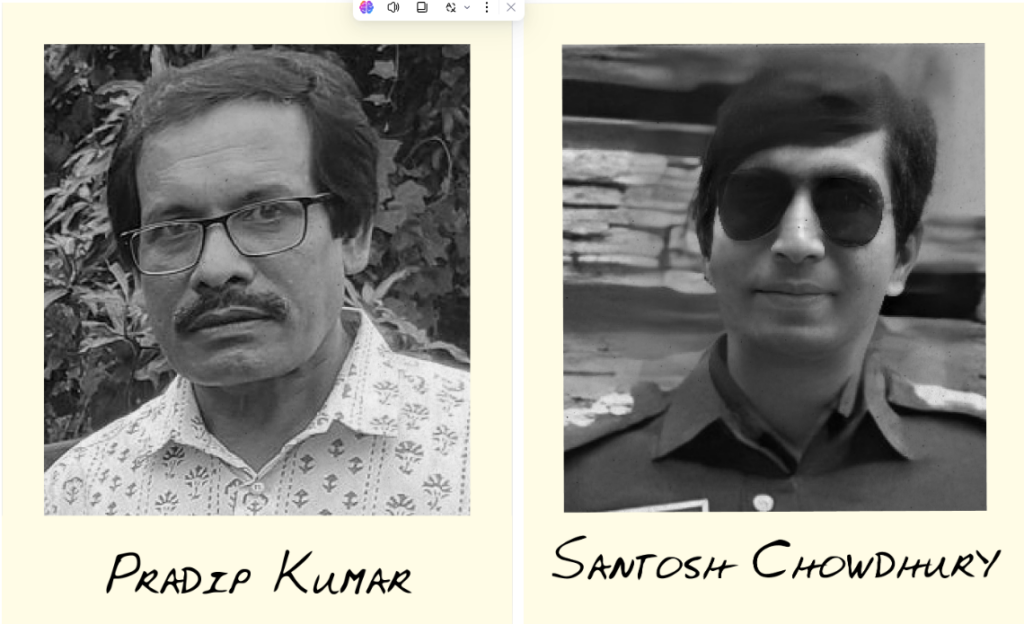

Pradip Kumar Bhowmik, a newspaper correspondent, was the fifth individual on the Unity Council’s list. He died on 4th August when he and five other Awami League activists—all Muslim men—were beaten to death around the premises of the Raiganj Press Club, located next to the Awami League office. The Unity Council cites itself as the source but does not explain why his death was classified as a religiously motivated murder while the deaths of the other five men were not.

Netra News spoke to M.H. Monayem Khan, a journalist who serves as the general secretary of the Raiganj Press Club, where the incident occurred. Khan—like Bhowmik—was trapped inside the press club that day but survived. “Pradip Da was with me as long as I was there,” he said.

According to Khan, attackers targeted the Awami League office adjacent to the press club and set fire to motorbikes parked in front. “As the fire spread, our choice was to die inside or to go out and get beaten,” he recounted.

In an attempt to save their lives, Khan and some colleagues jumped from a window, only to be seized by an angry crowd who beat them mercilessly. Bhowmik chose to exit through the front door, where another mob awaited.

Khan could not confirm why the press club came under attack. “But several Awami League leaders took shelter inside the press club,” he said. “That might have infuriated the attackers.” He insisted the assailants had little time to discern anyone’s religious identity before attacking. They targeted “anyone coming out of the club that day,” he said.

In the days leading up to the government’s overthrow, the police—implicated in the deaths of hundreds of protesters—became primary targets of public fury. On August 18th, police headquarters announced that 44 officers had been killed during the unrest, with only six being non-Muslims, according to an official document.

Among the slain was Sub-Inspector Santosh Chowdhury, a Hindu officer stationed at Baniachong Police Station in Habiganj. Just hours after Sheikh Hasina fled the country, a mob surrounded the police station, demanding justice for three individuals – including an underaged – killed by police earlier that day. During this upheaval, Chowdhury was beaten to death. The Unity Council classified his death as a communally motivated killing.

In its report, the organisation cited information about Chowdhury from Desh Rupantor, a national vernacular newspaper. However, the report itself did not indicate any religious motivation behind the incident.

Netra News interviewed three eyewitnesses—including two journalists who covered the event and a Hindu student—all disputed any communal motives in Chowdhury’s killing.

Abu Hanif, a fellow officer and colleague of Chowdhury, filed a complaint on 22nd August, detailing the extreme volatility leading up to his death. According to the complaint, a copy of which was obtained by Netra News, an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 people had gathered around the police station that day. Seven police officers, including Chowdhury, were seriously wounded before military personnel attempted a rescue from the besieged station. The mob did not discriminate by religious identity when targeting officers. Among the wounded were five Muslim officers: Sub-Inspectors Ruhul Amin, Humayun Kabir, and Mahmudul Hasan; Assistant Sub-Inspector Mohsin Miji; and Additional Police Superintendent Aminul Islam.

The complaint describes how the military calmed the mob—which had earlier been subjected to gunfire—and attempted to evacuate ten police officers one by one. During this process, a group seized Chowdhury, and the army was unable to rescue him before he was beaten to death.

Hafizur Rahman, the local correspondent for Prothom Alo, one of the country’s most respected newspapers, told Netra News that multiple accounts suggested Chowdhury was perceived by some locals as having implicated individuals in false drug-related cases and being particularly close to local Awami League members.

“Santosh befriended local Awami League and Chhatra League affiliates and allegedly used to arrest and torture people under their direction,” Hafizur explained, suggesting this may have fuelled the mob’s anger against him.

Badrul Alam, a reporter for Dainik Khowai, a local vernacular, agreed with the assertion.

Unclear motivation or mixed circumstances

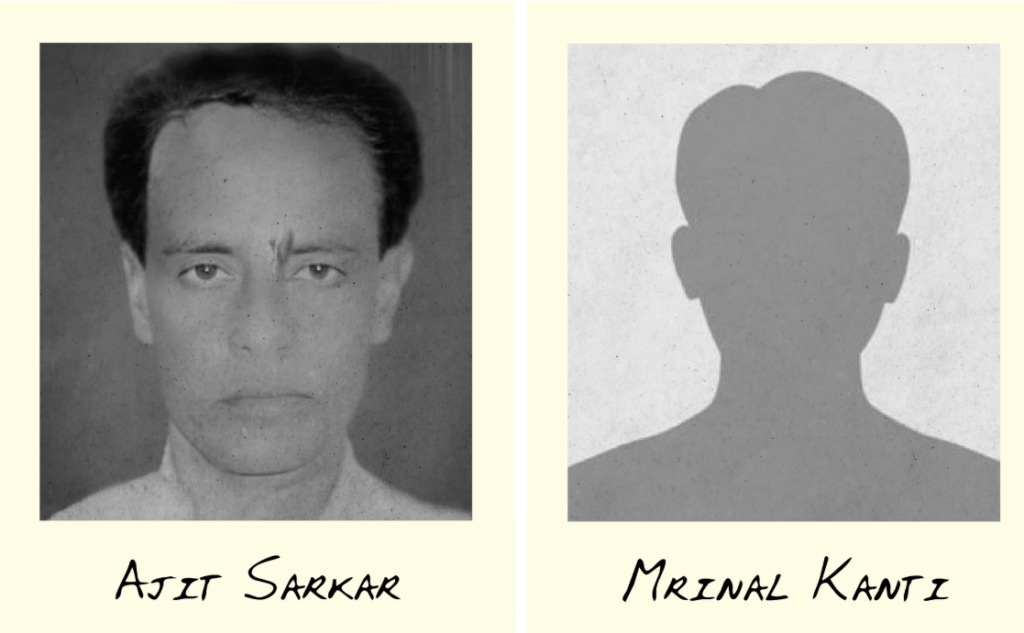

On August 5th, in Phulpur, Mymensingh, north of Dhaka, supporters of a local political figure allegedly killed Ajit Sarkar for having testified against the politician’s father at the International Crimes Tribunal. Netra News could not independently corroborate the claim against the political figure and has therefore withheld his identity.

The International Crimes Tribunal was a controversial court established by Sheikh Hasina’s government to prosecute crimes against humanity committed during Bangladesh’s 1971 war of independence. Ranadash Gupta, the Unity Council’s most prominent leader and co-president, served as one of its prosecutors. The tribunal primarily prosecuted individuals associated with the opposition BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami, leading to several death penalties and resultant executions.

In a conversation with Netra News, Sarkar’s wife, Purnima Rani, recounted that a group of men began attacking the houses of local Awami League leaders as soon as news of Hasina’s fall reached the village. “Around 4:30 pm, a mob started attacking houses of the Awami League’s leaders,” she said. “Soon, they reached our house too and struck my husband’s head,” she added.

Purnima Rani, her husband, and their children took shelter inside a room. As the mob grew larger, Ajit Sarkar decided to flee, fearing a more brutal attack on his life. He went to hide in a nearby home but was seized by the mob. She could not identify who had taken him away.

The Unity Council, citing itself as the source, claimed he was beaten to death, but his body has never been found, according to a local journalist, an activist with Unity Council’s student wing, and family members. “We haven’t found his body yet,” said Purnima Rani. “We heard he was beaten, then thrown into the river.” Prothom Alo, too, reported that his whereabouts were unknown.

“Those who beat him up that day on the riverbank said he swam across it,” a local journalist, who wished to remain anonymous, told Netra News. However, he found it hard to believe Ajit, a septuagenarian, could swim across the river.

Sarkar’s case appears to have strong political connotations due to his affiliation with the Awami League, his involvement with the tribunal’s proceedings, which largely targeted the party’s opponents, and the targeting of Awami League leaders in the area at the time, as her wife recounted.

While no evidence suggests that his disappearance, if not death, was religiously motivated, it is plausible that his identity as a Hindu may have emboldened his attackers to target him. Other family members and local Hindu community leaders who spoke to Netra News expressed fears for their safety if their identities were revealed. Despite the case’s political nature, Netra News refrains from categorically classifying it as purely politically motivated, given the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the case.

On August 5th, Mrinal Kanti Chatterjee, a septuagenarian and former high school teacher, was killed when a group attacked his home in the southern district of Bagerhat. News reports, including those from Prothom Alo, cited his wife, Shefali Chatterjee, and daughter, Jhuma Rani Chatterjee, who blamed neighbours named Humayun Sheikh and Nurul Islam.

The family had a longstanding legal dispute over land ownership with these neighbours—a case that had reached the High Court. Netra News reviewed two separate Facebook videos where Shefali reiterated these allegations to a group of minority rights advocates.

In the evening, “Nurul came with some people […] I have had a land-related dispute with them,” she was heard saying in one of the videos. “Then Humayun’s younger brother Miraz said, ‘Kill him now; we don’t have to fight the case in court.’” She added that some other neighbours protected her family at that time but alleged that the attackers returned later that night, resulting in Mrinal’s death and injuries to her daughter and herself.

In Bangladesh, one of the world’s most densely populated countries with complex land laws, disputes over scarce land are common. A 2020 paper found that 17% of its 35 million households had or have disputes over land parcels. According to the then-attorney general, 60% of Bangladesh’s four million civil legal disputes are related to land. These conflicts often span generations due to the overstretched legal system and can turn deadly between warring parties. Documentation by the Peace Observatory at Dhaka University found that from 2015 to 2020, one in 17 of the country’s total 20,466 homicides originated from land disputes, averaging more than 200 such killings a year.

While it’s plausible that the attackers felt emboldened after the fall of the Sheikh Hasina government, there is no clear evidence of religious or communal motivation behind the attack.

The Rapid Action Battalion has arrested Johny Sheikh, the principal man accused by Chatterjee’s family for his death, on September 16th. Humayun Sheikh, likely related to Johny, and Nurul Islam, who were named by Shefali Chatterjee, remain on the loose.